Jane Austen’s Hidden Feminism

Posted on June 7, 2018

by Rebecca S

Jane Austen’s Pride and Prejudice

|

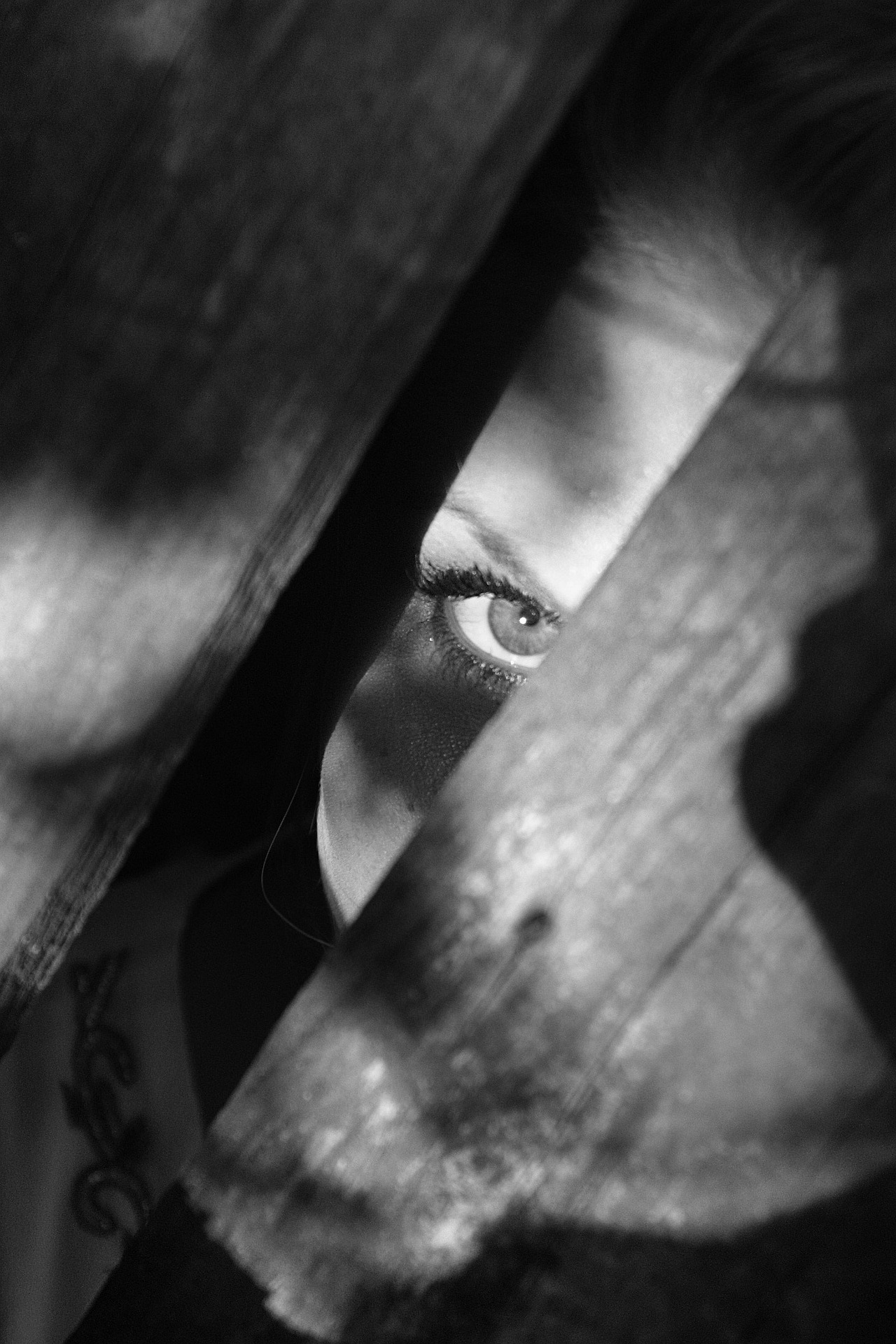

“Pride and Prejudice,” a book that will live in infamy and also appears on a recent list of 100 Great American Reads, is a lot more feminist than popular culture would have you believe, and so is its author. I didn’t know this when I first read the novel at 13 or 14. I didn’t know what it meant that Elizabeth openly defied traditional gender norms. It surprised me that Mary, the often-ignored Bennet sister reached for learning beyond what was considered appropriate for a woman. And I overlooked the significance of how radical it was that Charlotte, after marrying the overbearing Mr. Collins, was able to maintain a degree of independence when one would expect her to lose all autonomy. But after years of living with “Pride and Prejudice,” as well as all of Austen’s novels, revisiting them and the world in which Austen lived – it is clear that Austen was a rebel, a radical and a feminist. |

The Dangers of Being a Female Author

Jane Austen is often cited by critics as an author whose books were far removed from the reality of her time – that they rarely reflected the state of war that Britain was in for most of her life or the social and political changes happening at a rapid pace. But this could not be further from the truth. Austen did reveal her beliefs, not just about domestic life and relationships, but about the wider political and social issues of the day. She did so warily and subtly, but with the understanding that her readers would know how to read between the lines and mine her books for meaning. Austen’s subtlety and coded language is due in large part to necessity. Austen lived in a world where the roles of women were so tightly controlled by men, that women writers had to tread ever so carefully. Austen was aware of what could and would happen if she stepped a foot into the seemingly “improper” – she had plenty of contemporary examples. The reputation of the feminist writer Mary Wollstonecraft had been destroyed after her death in 1797. Rumors circulated that Ann Radcliffe, the author of “The Mysteries of Udolpho“—Catherine Morland’s favorite novel in “Northanger Abbey“—had gone insane. Charlotte Smith anticipated that some people would find the political commentary in her 1792 novel, “Desmond” disturbing coming from a woman. And she was proven right when Smith’s defense of the principles of the French Revolution saw the novel rejected by her usual publishers and her place in society questioned. Even Maria Edgeworth, the most successful novelist of the period, was forced to rewrite her 1801 novel “Belinda” to remove a marriage that critics thought morally dangerous because one character was white and the other black. |

Modern Misrepresentation

|

This inability of modern readers to understand Austen is mostly due to the modern view of sex and marriage. Marriage as Austen knew it involved a woman giving up everything to her husband—her money, her body, her very existence as a legal adult. Husbands could abuse their wives, imprison them or even take their children away all within the bounds of the law. When readers start to understand what a serious subject marriage was to Austen and to women of her time, then suddenly the courtship plots look like a much more serious matter. Marriage mattered because it was the defining action of a woman’s life. To accept or refuse a proposal was almost the only decision that a woman could make for herself, because it was the only way to exert control over her life. Austen’s novels aren’t romantic. But it’s become increasingly difficult for readers to see this. These misrepresentations make us read novels that are not actually there; and worse they make us deny Austen the image and the life she created for herself. Imposing on her a literary reputation that denies her radicalism, her feminism and resigns her pop culture romantic purgatory. |

The Radical Austen

|

If we want to be the best readers of Austen’s novels that we can be, the readers that she hoped for, then we must take her seriously. We can’t shrug off apparent contradictions or look only for confirmation of what we think we already know about her and her novels. We must read, and we have to read carefully. Because Austen had to write carefully. She was living in a time when ideas both scared and excited people – especially when those ideas were presented by a woman questioning the very foundation of British society. A society in which parents and guardians openly made selfish decisions regarding their children’s lives; in which the Church ignored the needs of the faithful; in which landowners and magistrates—the people with local power—were eager to enrich themselves even when that meant driving the poorest into criminality; and in which women were used as currency and leverage by men to gain money and produce heirs. Austen’s novels, in truth, are as revolutionary as anything that Wollstonecraft or Thomas Paine wrote. But by and large, the novels are so cleverly crafted that unless readers are looking in the right places—reading them in the right way—they simply won’t understand. |

Jane Austen’s Novels

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Non-Fiction About Austen and Her World

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Did you like this blog post? Keep up to date with all of our posts by subscribing to the Library’s newsletters!

Keep your reading list updated with our book lists. Our staff love to read and they’ll give you the scoop on new tv-series inspired titles, hobbies, educational resources, pop culture, current events, and more!

Looking for more great titles? Get personalized recommendations from our librarians with this simple form.